What is the UK Monetary Supply?

10/10/2024Daniel Fisher

Free & fully insured UK Delivery. Learn more

Secure & flexible payments. Learn more

Buyback Guarantee Learn more

Money is at the heart of any economy, and understanding how it flows through a country is essential for grasping the basics of economic health and policy.

In the UK, the monetary supply refers to the total amount of money circulating in the economy, including physical cash, bank deposits, and other forms of easily accessible funds such as gold bullion. But what exactly does this mean, and how is it measured?

We break down the various components of the UK’s monetary supply and how it can influence interest rates and quantitative easing.

The UK monetary supply refers to the total amount of money available within the economy, covering both liquid forms (cash and demand deposits) and broader financial assets that can be converted into cash, including gold reserves. To measure the money supply, economists typically categorize it into different levels, such as M0, M1, M2, and M3. Each level represents varying degrees of liquidity and accessibility.

Here’s how the UK’s monetary supply is broken down:

This is the narrowest measure and includes all physical currency (notes and coins) in circulation, as well as the reserves held by the Bank of England. M0 represents the foundation of the money supply, directly controlled by the central bank.

M1 includes M0 plus the most liquid forms of money, such as instant access deposits (current accounts) that can be easily accessed for spending. This measure focuses on the cash readily available for everyday transactions.

M2 expands on M1 by including savings accounts, short-term time deposits, and money market funds that, while not as liquid as M1, can still be converted to cash relatively quickly. M2 gives a broader view of the money available in the economy.

M3 is the broadest measure of money supply, incorporating M2 along with larger, less liquid financial instruments, such as institutional money market funds and long-term deposits. Though not as widely used in the UK today, M3 provides a more comprehensive view of all money in the financial system, including longer-term holdings.

The UK’s money supply is a key indicator of the country’s economic health, helping policymakers understand the flow of money through the economy. By tracking different measures of the money supply, such as M1, M2, and M3, economists can gauge the availability of liquid funds and the broader financial assets that support economic activity.

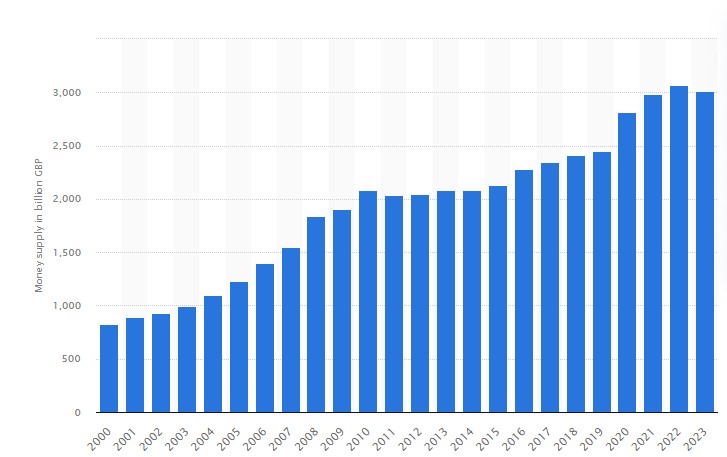

As of the most recent 2024 figures from the Bank of England:

The M2 money supply in the UK, which includes cash, instant access deposits, and savings accounts, stands at approximately £2.6 trillion.

The M3 money supply, a broader measure that includes M2 plus large deposits and other long-term financial assets such as the UK’s gold reserves, is estimated to be around £3.1 trillion.

The fluidity of the monetary supply is demonstrated by the way figures have varied during recent marco-economic events. These trends reflect how external events and central bank policies impact the money supply, shaping both short-term economic conditions and long-term growth.

Over the past few years, the UK’s monetary supply has seen notable changes, influenced by factors such as:

The Bank of England’s quantitative easing programs, particularly during economic crises like the 2008 financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, have significantly increased the monetary base by injecting more money into the economy. This expanded the overall money supply, particularly M0 and M2.

As the UK recovered from the pandemic, the monetary supply growth has slowed compared to the aggressive expansions seen during QE. However, supply remains elevated due to continued low interest rates and stimulus efforts such as the infamous Bounce Back Loans.

Rising inflation has prompted concerns about controlling the money supply, with the Bank of England tightening monetary policies, which can reduce the overall money flow and stabilize prices. This can help control demand-driven inflation but has less effect on supply-inflation as witnessed in recent years due to oil and gas challenges.

Value of M2 Money Supply in UK 2000-2023 (Source: https://www.statista.com/)

Understanding the UK’s monetary supply is critical because it directly affects key aspects of the economy, such as inflation, interest rates, and economic growth. The UK’s monetary supply serves as a critical tool for managing the economy, ensuring a balance between growth and stability. Here’s why it matters:

Too much money circulating in the economy can lead to inflation, where the value of money decreases, and prices for goods and services rise. By monitoring and adjusting the money supply, the Bank of England can help control inflation and maintain price stability.

The money supply influences the cost of borrowing. When there is more money available, interest rates tend to be lower, encouraging borrowing and investment. Conversely, a tighter money supply can lead to higher interest rates, curbing excessive borrowing and controlling inflation.

A balanced money supply supports healthy economic growth by ensuring that businesses and consumers have access to credit and liquidity. This helps fuel investments, job creation, and spending, driving overall economic activity. Squeezing money supply for too long can lead to a so-called “hard landing” for the economy whereby growth slows to a halt.

Managing the money supply is key to maintaining stability in the banking system. Too little money can cause financial crises, while too much can lead to bubbles and instability.

Download the Insider's Guide to UK Gold Investment

The Monetary Base, also known as M0, is the foundation of the entire money supply and plays a critical role in the overall stability of the UK economy. It represents the most liquid form of money, consisting of cash and central bank reserves.

The monetary base, or M0, is the narrowest measure of the money supply and includes:

This includes all the physical cash (notes and coins) that is in the hands of the public and businesses. It is the most visible part of the monetary base that people use for everyday transactions.

These are deposits that commercial banks hold at the Bank of England. Reserves act as a buffer to ensure banks have enough liquidity to meet their obligations. The central bank uses reserve requirements and interest rates on reserves to influence how much money commercial banks can lend out, thereby affecting the broader money supply.

Unlike broader measures of money supply (like M1, M2, and M3), the monetary base is tightly controlled by the Bank of England. By managing M0, the central bank influences liquidity in the financial system and can implement policies to stimulate or restrict the economy as needed.

The monetary base serves as the foundation from which broader money supply measures grow. When commercial banks lend out reserves, they expand the money supply, leading to the creation of more money in the form of deposits and credit.

Central banks play a crucial role in shaping the flow of money in an economy by using a range of tools to manage the monetary supply. Their primary goal is to maintain economic stability by controlling inflation, ensuring adequate liquidity, and supporting sustainable economic growth.

In the UK, the Bank of England is responsible for these functions, adjusting the money supply through various policies and mechanisms.

Central banks like the Bank of England have several key tools to control the money supply. In the UK, many of these functions are performed by the Bank of England’s Monetary Policy Committee (MPC).

By raising or lowering the base interest rate, central banks influence borrowing and lending in the economy. A lower interest rate makes borrowing cheaper, encouraging businesses and consumers to take out loans, which increases the money supply. Conversely, higher interest rates discourage borrowing and reduce the money supply. The MPC meet eight times a year to decide on these rates. Prior to 6 May 1997, rates were set by the UK Government, but it was felt that granting independent control of rates would detach decisions from any political agenda.

Central banks buy or sell government securities (like bonds) in the open market to adjust the money supply. When the central bank buys securities, it injects money into the economy, increasing liquidity. Selling securities does the opposite, pulling money out of circulation.

Central banks set the minimum reserves that commercial banks must hold. This is a precaution to cover defaults on bank loans and ensure bank liquidity and security. By lowering reserve requirements, the central bank allows banks to lend more money, expanding the money supply. Raising reserve requirements reduces the amount banks can lend, shrinking the money supply.

This is a more unconventional tool used during times of economic crisis but has become a household term due to the credit crunch of the mid 2000s and the COVID-19 pandemic. The central bank buys financial assets (such as government and corporate bonds) from banks and other financial institutions to increase liquidity in the financial system. Quantitative Easing (QE) dramatically expands the money supply, as it injects large amounts of money into the economy. Prolonged and aggressive QE programs can have the side effect of depreciating currency, leading to increased demand for more inflation-hardened assets such as gold.

Gold has historically played a central role in the global monetary system, once acting as the direct backing for currency under the gold standard.

While modern economies like the UK no longer use gold to directly back their currency, it remains an important reserve asset for central banks, including the Bank of England as it provides stable store of value and a hedge against economic uncertainty.

Gold no longer directly forms part of the monetary base in modern economies. Under the historic gold standard, currency was backed by gold, meaning governments had to hold equivalent gold reserves to match the amount of money in circulation. Today, currencies are no longer tied to gold, and the monetary base consists of physical currency and central bank reserves.

However, gold still plays an indirect role in the financial system as a reserve asset held by central banks. It is not considered part of the money supply (like M0, M1, M2, or M3), but it remains a key financial asset. This blurs the line between gold being a commodity or a currency.

Central banks hold gold not only to diversify but also as a hedge against inflation, currency devaluation, and other financial risks. Gold provides stability in times of economic turmoil, as it tends to retain or even increase its value when paper currencies fluctuate.

The Bank of England holds a significant portion of the UK’s foreign reserves in gold, making it a crucial component of the country’s financial stability strategy. While gold is not part of the monetary base, it is held as part of the UK’s central bank reserves, which also include foreign currencies and government bonds.

As of recent data in 2024, the Bank of England holds approximately 310 tonnes of gold in its reserves. Timing gold accumulation and sales can be crucial due to unpredictable market cycles, as highlighted by the infamous “Brown’s Bottom” phase between 1999 and 2002. This was when the UK’s Gordon Brown sold half the UK’s gold when prices were at their lowest level in two decades.

Gold reserves serve multiple purposes:

In times of crisis or uncertainty, gold can be used to bolster confidence in the economy. It is often seen as a “safe haven” asset that retains value, even when other assets decline.

Gold is an important part of the central bank’s portfolio, offering diversification from traditional financial assets like government bonds and foreign currency reserves.

Gold reserves can also be used in international trade and finance, helping to settle debts or provide collateral for loans between countries.

As the world becomes increasingly digital, the way people interact with money is evolving. Digital currencies and payment systems have become a growing part of the financial landscape, offering faster and more convenient ways to transact. While cryptocurrencies, such as Bitcoin, are not yet considered part of the official UK money supply, their impact on the broader economy is significant and growing.

Central banks, including the Bank of England, are actively exploring how digital currencies might fit into the future of money, potentially reshaping the monetary supply and financial systems.

In recent years, the UK has seen a rapid shift toward digital payments, driven by the rise of online banking, mobile payment apps, and contactless technology. Key trends include:

The use of physical cash is steadily declining, with more consumers opting for digital transactions using debit and credit cards, mobile wallets (like Apple Pay and Google Pay), and online banking. As of 2023, over 80% of UK transactions are now cashless, reflecting the increasing dominance of digital payment methods. Many feel the intrinsic value of gold can still play a role in a cashless society.

Digital payment systems, such as the UK’s Faster Payments service, allow individuals and businesses to transfer money instantly, improving liquidity and speeding up the flow of money across the economy. These digital transactions contribute to M1 and M2 money supply figures, as they represent deposits and easily accessible funds.

The Bank of England, along with many of the globe’s leading central banks, is exploring the potential introduction of a “digital pound”, also known as a CBDC. This would be a digital form of central bank money, designed to coexist with physical cash and commercial bank deposits, potentially becoming part of the monetary base. A digital pound could further modernize the UK’s payment system and bring more flexibility to monetary policy.

Our automated portfolio builder will provide suggestions based on various investment objectives

Cryptocurrencies, like Bitcoin and Ethereum, have gained significant attention over the past decade, offering a decentralized, digital alternative to traditional currencies. While cryptocurrencies are not currently recognized as legal tender in the UK and are not part of the official money supply (M0, M1, M2, or M3), they have a growing impact on the economy in several ways:

Many individuals and institutional investors in the UK have turned to cryptocurrencies as an asset class, hoping to profit from their price volatility. This has led to an influx of capital into the crypto markets, contributing to broader financial speculation and investment trends.

Cryptocurrencies are the foundation of DeFi platforms, which offer decentralized financial services like lending, borrowing, and trading without traditional intermediaries such as banks. These innovations are creating new opportunities for financial inclusion but also present regulatory challenges.

The UK government and the Bank of England are closely monitoring the growth of cryptocurrencies and are in the process of developing regulations to ensure they do not destabilize the financial system. While the current impact of crypto on the UK’s official money supply is limited, its increasing use in commerce, investment, and technology could shape the future of finance.

As digital currencies and payment systems continue to evolve, their role in the UK’s monetary supply and economy will likely grow, with central banks needing to adapt their policies to keep pace with technological advancements.

M1 includes the most liquid forms of money, such as cash, demand deposits, and traveller’s checks. M2 encompasses M1 plus less liquid assets like savings accounts, time deposits, and money market funds. Essentially, M2 represents a broader measure of the money supply, capturing both easily accessible cash and savings that can be quickly converted into cash.

The monetary base (M0) includes physical currency in circulation and reserves held by banks at the central bank. The money supply includes the monetary base plus liquid assets like deposits (M1, M2, M3), representing the total money available in the economy for spending, saving, and investment.

As of recent data, there are over 4.9 billion Bank of England notes in circulation, with a total value of approximately £91 billion. This includes physical cash (notes and coins) used for transactions across the UK, though the use of cash has been steadily declining due to the rise of digital payments.

Gold is no longer directly part of the UK monetary supply. Under the gold standard, currency was backed by gold, but modern economies, including the UK, use fiat currency which isn’t linked to gold. However, gold is held in the UK’s central bank reserves as a store of value and a hedge against financial risks.

Yes, the Bank of England holds around 310 tonnes of gold as part of its reserves. While gold isn’t part of the money supply, it’s a crucial asset for financial stability, helping to diversify reserves and act as a safeguard during economic uncertainty.

The UK, like most countries, moved away from the gold standard in the 20th century because it restricted monetary flexibility. Today, the money supply is based on fiat currency, which gives central banks more control over the economy by adjusting interest rates and managing the supply of money without needing to tie it to gold.

Gold reserves provide a safety net during financial crises, offering a stable asset that retains value when other assets, like currencies or stocks, may fluctuate. They also help diversify the UK’s central bank reserves, which include foreign currencies and government bonds, enhancing financial security.

Live Gold Spot Price in Sterling. Gold is one of the densest of all metals. It is a good conductor of heat and electricity. It is also soft and the most malleable and ductile of the elements; an ounce (31.1 grams; gold is weighed in troy ounces) can be beaten out to 187 square feet (about 17 square metres) in extremely thin sheets called gold leaf.

Live Silver Spot Price in Sterling. Silver (Ag), chemical element, a white lustrous metal valued for its decorative beauty and electrical conductivity. Silver is located in Group 11 (Ib) and Period 5 of the periodic table, between copper (Period 4) and gold (Period 6), and its physical and chemical properties are intermediate between those two metals.